Premenstrual dysphoric disorder, or PMDD, is a severe psychiatric condition that affects millions of menstruating people across the United States, yet remains poorly recognized and frequently dismissed as ordinary hormonal mood swings. The condition is characterized by intense depressive episodes, uncontrollable rage, debilitating anxiety, and suicidal ideation that appear cyclically during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, the two weeks between ovulation and menstruation, then resolve within days of menstruation starting.

For those who suffer from PMDD, the experience is catastrophic: they lose weeks of their life to a condition they cannot control, relationships collapse under the weight of mood swings they cannot explain, work performance crashes due to severe fatigue and cognitive dysfunction, and many contemplate ending their lives during their most difficult weeks. Understanding PMDD as a legitimate medical disorder rather than personal weakness is critical, because the research is unambiguous: women with PMDD have nearly seven times the risk of suicide attempt and four times the risk of suicidal ideation compared to those without the condition.

This article provides a comprehensive look at what PMDD is, the neurobiological mechanisms driving it, the devastating impact on peoples lives, and the evidence-based treatments that work.

Key Points (2026)

- PMDD is a psychiatric disorder affecting 1.8 to 5.8% of U.S. menstruating people annually: Meta-analysis research shows confirmed diagnosis prevalence ranges from 1.6% to 3.2%, meaning approximately 2.3 million American women meet diagnostic criteria each year.

- Approximately 80% of menstruating people experience some premenstrual symptoms, but only 3-8% develop PMDD: The distinction is crucial: mild premenstrual syndrome affects tens of millions; PMDD represents a subset with severe, disabling symptoms that require psychiatric intervention.

- Women with PMDD have 6.97 times higher risk of suicide attempt and 3.95 times higher risk of suicidal ideation: According to meta-analysis of 13 studies, these elevated risks persist even after accounting for depression, PTSD, and other mental health conditions, indicating that PMDD itself carries independent suicide risk. In one comprehensive study, 72% of PMDD participants reported lifetime suicidal ideation, 49% had made plans, and 34% had attempted suicide.

- PMDD causes significant functional impairment across multiple life domains: Research shows 100% of women with PMDD report fatigue or lack of energy; over 70% report impaired work or school productivity; relationship disruption occurs in 22% more PMDD cases than non-PMDD cases in a study of 15,000 women. Women miss over 8 hours per menstrual cycle due to symptoms, costing employers approximately 4,000 dollars USD annually in absenteeism and presenteeism.

- PMDD is rooted in abnormal brain sensitivity to normal hormonal fluctuations, not hormone deficiency: Neurobiological research has identified that women with PMDD possess genetic variations affecting emotional regulatory pathways, making them hypersensitive to estrogen and progesterone fluctuations; additionally, abnormal sensitivity to allopregnanolone (a progesterone metabolite) can paradoxically increase anxiety instead of providing the calming effect seen in non-PMDD populations.

- Treatment is highly effective, with 60-75% experiencing significant improvement: First-line treatments include SSRIs (taken luteal-phase cyclically or continuously), hormonal birth control, and cognitive-behavioral therapy; response rates are substantially higher than for general depression, and cyclical dosing minimizes unnecessary medication exposure.

What Is PMDD: Definition and Clinical Significance

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder is a mood disorder characterized by a cyclical pattern of severe emotional, cognitive, and physical symptoms that emerge during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and resolve shortly after menstruation begins. The condition was formally recognized in the DSM-5 in 2013 as a depressive disorder, distinguishing it from premenstrual syndrome and establishing it as a legitimate psychiatric diagnosis warranting clinical intervention.

The defining feature of PMDD is the predictable cyclical pattern combined with severity and functional impairment. A woman with PMDD does not simply feel sad or irritable in the days before her period; rather, she experiences a psychiatric crisis that disrupts her ability to work, maintain relationships, care for herself, and in severe cases, threatens her life. The symptoms are not attributable to stress, poor coping skills, or personality weakness. They emerge from alterations in brain chemistry and structure related to how an individual’s brain processes reproductive hormones.

The 2025 meta-analysis examining global prevalence of PMDD found that when studies use strict DSM-5 diagnostic criteria applied prospectively to community-based samples, confirmed PMDD prevalence is 1.6% (95% confidence interval 1.0% to 2.5%). However, provisional diagnoses and clinical samples show higher rates of 3.2% to 7.7%, suggesting that when mild or unconfirmed cases are included, prevalence increases substantially. In the United States specifically, North American samples show a pooled prevalence of 2.8%, lower than the global average but representing millions of women.

Translating these prevalence rates to the U.S. population: approximately 2.3 million menstruating women in the United States meet diagnostic criteria for PMDD annually. This population experiences an average of 168 hours (over one week) of severe symptoms per menstrual cycle, meaning PMDD accounts for roughly two to four weeks of non-functionality per year for each affected individual. 45 Over a 30-year reproductive lifespan, this represents roughly five to ten years of lost productivity and quality of life to a preventable, treatable condition.

Historical Recognition and Global Impact

PMDD was officially recognized by the World Health Organization in 2019 when it was added to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision (ICD-11) with its own disease code (GA34). This recognition was a watershed moment, signaling that PMDD is not a Western medical construct or psychiatric overreach but a globally significant health burden affecting women across cultures and economic systems.

Yet despite this official recognition, PMDD remains profoundly underdiagnosed and undertreated. A 2025 narrative review in Frontiers of Psychiatry analyzing the burden of PMDD documented a “vicious cycle” where limited awareness and recognition lead to minimal research funding, which in turn produces limited treatment development and public education, perpetuating underdiagnosis. The review highlighted that Latin America, despite populations potentially facing higher PMDD prevalence due to socioeconomic stressors and limited mental health resources, has essentially no recent epidemiological data because PMDD receives almost no research attention in those regions. This represents a global health equity crisis: the women most burdened by economic precarity and limited healthcare access face the highest barriers to PMDD recognition and treatment.

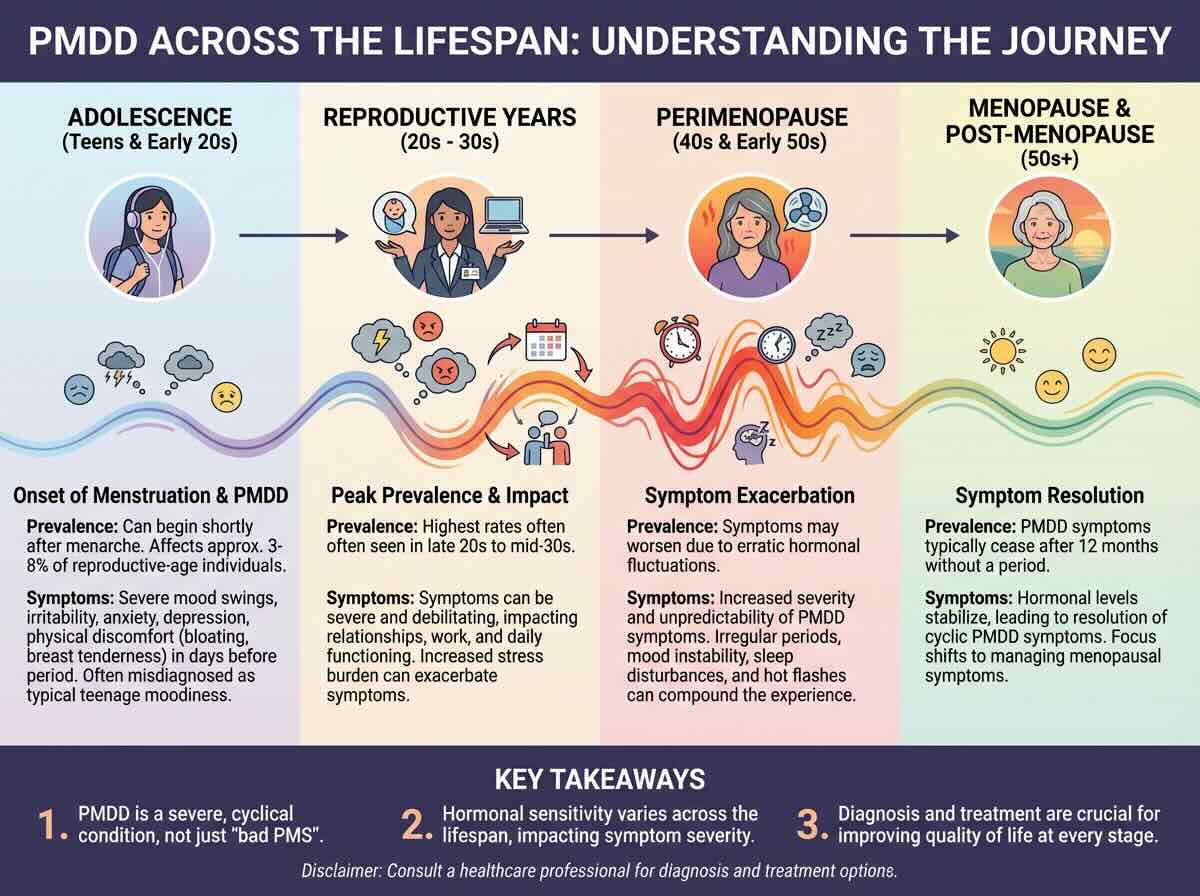

PMDD Across the Lifespan: From Menarche to Menopause

Because PMDD is a reaction to the ovulatory cycle, its presence is strictly confined to the years in which a person is menstruating. However, the intensity and presentation of symptoms evolve significantly across different life stages.

The Onset: Adolescence

PMDD can emerge as early as menarche (the first menstrual period). In teenagers, however, the disorder is frequently overlooked or dismissed as “normal puberty” or “teen angst.” Research indicates that early-onset PMDD can be particularly devastating, as it interferes with critical periods of social and academic development during the teenage years.

The Peak: 20s and 30s

Most clinical diagnoses occur between the ages of 25 and 35. This is often the period when the cyclical nature of the symptoms becomes undeniable. Over a decade of “bad weeks,” women begin to recognize the pattern, leading them to seek psychiatric help. It is also a high-risk period for reproductive transitions; women with PMDD are significantly more likely to experience severe Postpartum Depression (PPD) after childbirth, as the brain struggles with the massive hormonal crash following delivery.

The “Final Flare”: Perimenopause

Counterintuitively, PMDD symptoms often reach their maximum severity in the 40s. During perimenopause, the fluctuations of estrogen and progesterone become increasingly erratic and “jagged.” For a brain already hypersensitive to hormonal change, this volatility can lead to the most severe psychiatric crises an individual has ever faced. Many women describe this stage as a “second puberty” but with significantly higher stakes regarding their careers and families.

Resolution: Menopause

The “cure” for PMDD is the cessation of the menstrual cycle. Once a woman reaches menopause and the ovaries no longer produce the cyclical peaks and valleys of progesterone, PMDD symptoms resolve. This biological fact confirms that the disorder is not a permanent personality trait or a general depressive disorder, but a specific, triggered reaction to a functioning reproductive system.

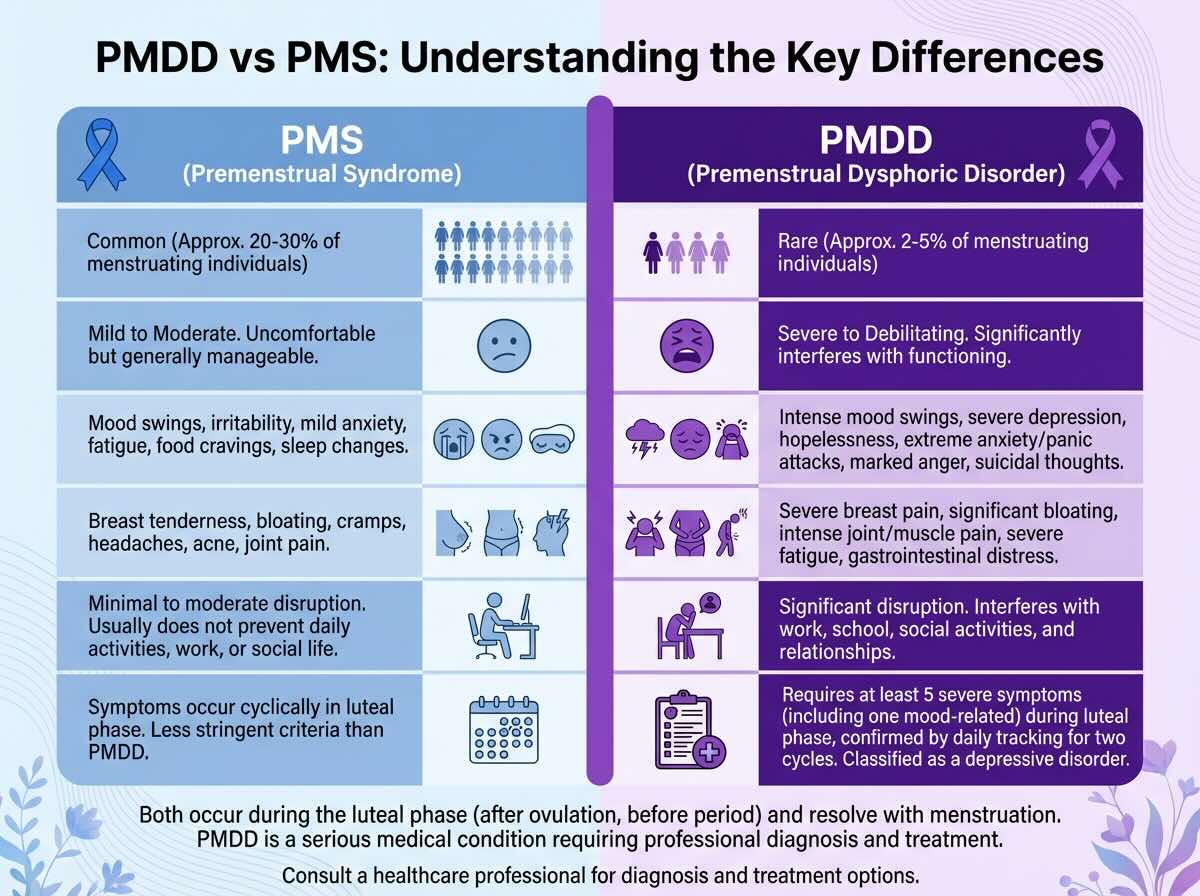

PMDD vs. PMS: Understanding the Critical Distinctions

The confusion between PMDD and premenstrual syndrome is understandable because they exist on a spectrum of premenstrual symptomatology, yet they are fundamentally different conditions in severity, mechanism, and treatment requirements. Approximately 80% of menstruating women experience some physical, emotional, or behavioral symptoms in the week before menstruation; 20% to 40% report moderate-to-severe symptoms; and 3% to 8% experience PMDD. Understanding where an individual falls on this spectrum is clinically critical because the approach to treatment differs substantially.

| Clinical Parameter | Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) | Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) |

|---|---|---|

| Population Prevalence | 80% of menstruating women report some symptoms; 20-40% report moderate-to-severe PMS. | 3-8% of menstruating women; approximately 2.3 million American women annually. |

| Symptom Severity | Mild to moderate irritability, bloating, mild mood sensitivity, food cravings, fatigue that does not prevent functioning. | Severe, disabling symptoms: uncontrollable rage, suicidal ideation, complete inability to function at work or school, severe anxiety, profound hopelessness. |

| Required Diagnostic Features | One or more symptoms present; can be physical alone without mood changes. | At minimum 5 of 11 specific symptoms, with mandatory inclusion of at least one of four key mood symptoms: marked mood swings, marked irritability/anger, marked depressed mood, or marked anxiety. |

| Timing Pattern | Onset typically 5-11 days before menstruation; resolves within 2-3 days of period starting. | Begins 5-7 days before menses, peaks 2 days prior and during first days of menstruation, resolves within a few days to one week after menstruation starts. |

| Functional Impact | Daily activities, work, and relationships continue; symptoms are inconvenient but manageable. Most people maintain normal functioning. | Severe disruption: over 70% report work or school impairment; 100% report fatigue; many cannot leave home during worst days; relationships suffer acute strain during luteal phase; suicide risk increases. |

| Duration per Cycle | Approximately 7-10 days per menstrual cycle. | Up to 14 days per cycle; for some women, nearly half the month is affected. |

| Treatment Approach | Lifestyle modifications (exercise, stress reduction, dietary calcium and magnesium, sleep) are often sufficient; over-the-counter pain relief for physical symptoms. | Requires psychiatric intervention: SSRIs (luteal-phase or continuous), hormonal contraceptives, cognitive-behavioral therapy, or combination approaches. Lifestyle changes alone are inadequate. |

| Clinical Recognition | Recognized as a medical condition but not a psychiatric disorder; often managed without professional involvement. | Formal psychiatric diagnosis in DSM-5; recognized by WHO in ICD-11; requires clinical assessment and treatment plan. |

The distinction in this table reveals an essential truth: PMS and PMDD are not points on a simple spectrum where “more severe PMS” becomes PMDD. Rather, PMDD represents a qualitatively different psychiatric condition. A woman with moderate PMS might feel irritable for a few days and experience fatigue; she still manages work, relationships, and self-care. A woman with PMDD enters a psychiatric crisis where these basic functions become impossible. This categorical difference justifies the different treatment approaches.

The Full Clinical Picture: Symptoms and Their Severity

PMDD involves a constellation of mood, behavioral, cognitive, and physical symptoms that emerge together during the luteal phase. The DSM-5 specifies 11 possible symptoms, of which at least five must be present for diagnosis, with mandatory inclusion of at least one mood symptom. What the diagnostic criteria do not fully convey is the intensity and disruptiveness of these symptoms when they occur. Understanding the actual lived experience of PMDD requires examining each domain of symptoms and their real-world impact.

Core Mood Symptoms: The Psychiatric Crisis

Marked affective lability (mood swings): Women with PMDD describe sudden, unpredictable mood changes that shift from moment to moment without external trigger. They may feel tearful, vulnerable, or deeply sad within minutes; these shifts feel involuntary and terrifying because the intensity feels disproportionate to the situation. A minor comment from a colleague triggers an emotional response equivalent to a major life crisis. The emotional dysregulation feels like loss of self-control, which itself produces anxiety and shame.

Marked irritability and anger: This is frequently described as the most disruptive symptom by women with PMDD. The irritability is not ordinary impatience; it is an all-consuming rage that feels uncontrollable and disproportionate. Small inconveniences (traffic, a misplaced item, a partner’s innocent comment) trigger explosive anger that the woman recognizes as unreasonable even as it is happening. Many women describe feeling “not themselves,” as if they are possessed by a different personality. Relationship devastation occurs during these episodes: partners are subject to verbal abuse, accusations, and rage that damages trust and intimacy. Women often report apologizing profusely after an episode, recognizing the disproportionality, yet feeling helpless to control the next eruption.

Marked depressed mood: During the luteal phase, women with PMDD experience profound depression characterized by pervasive sadness, hopelessness, worthlessness, and inability to envision improvement. Unlike depressive episodes in major depressive disorder, which can be triggered by life stressors or emerge without clear cause, PMDD-related depression is absolutely predictable, cyclical, and tied to the menstrual calendar. Women often experience depressive thoughts with full awareness that they will resolve after menstruation, yet in the moment, the depression feels absolute and inescapable. The knowledge that “this will pass in a few days” provides some cognitive framework but little emotional relief during the episode.

Marked anxiety and tension: Women describe feeling “keyed up,” unable to relax, experiencing constant tension in the body, and struggling with a sense of dread or foreboding without clear cause. Some experience full panic attacks during the luteal phase, with physical symptoms (racing heart, shortness of breath, chest pain, dizziness) that feel life-threatening. Anxiety sensitivity is elevated, meaning normal bodily sensations are interpreted catastrophically, which amplifies anxiety further.

Cognitive and Behavioral Symptoms: Functioning Deteriorates

Marked difficulty concentrating: During the luteal phase, women with PMDD report severe brain fog, inability to focus despite effort, memory problems that extend to difficulty retaining information from moments before, and inability to complete complex tasks. This is not laziness or poor motivation; it is a genuine cognitive impairment. Women in demanding professions report significantly decreased work output during luteal phase.

Marked loss of interest in usual activities: Activities that normally bring pleasure or satisfaction become emotionally empty or feel burdensome during the luteal phase. Social withdrawal occurs not from social anxiety but from profound disinterest and emotional numbness. Hobbies feel pointless. Work projects that normally engage interest feel tedious. This withdrawal can make the depressive episode worse by eliminating the distracting and mood-lifting effects of pleasurable activities.

Sense of being overwhelmed or out of control: Women describe feeling that demands exceed their capacity, that they cannot cope, that everything will fall apart. This overwhelm is not simply pessimism; it reflects genuine functional limitations during the luteal phase. The combination of severe mood symptoms, cognitive impairment, and fatigue means that normal daily demands do feel genuinely overwhelming.

Physical Symptoms and Sleep Disruption

PMDD includes physical symptoms that, while more tolerable than mood symptoms, contribute significantly to disability: joint and muscle aches, breast tenderness, bloating with sensation of weight gain, and headaches. Additionally, approximately 80% of women with PMDD experience sleep disturbance, manifesting as insomnia (inability to fall asleep or early morning waking despite opportunity for sleep), hypersomnia (sleeping excessively yet remaining fatigued), or disrupted, non-restorative sleep.

The sleep deprivation amplifies mood symptoms: depressed mood worsens, irritability increases, and cognitive impairment becomes more severe. Many women report that sleep disturbance is the initiating symptom; once sleep is lost, the mood cascade follows.

Appetite and Metabolic Changes

Many women report marked increases in appetite and specific cravings, often for carbohydrates and sugar, during the luteal phase. Some experience binge eating episodes. These changes in appetite and metabolic rate may reflect the brain’s attempt to increase serotonin through dietary means, as carbohydrates facilitate tryptophan entry into the brain. While appetite changes are less disabling than mood symptoms, they contribute to the overall experience of loss of control and can result in weight gain, which triggers additional shame and body image disturbance in some women.

The Critical Symptom: Suicidal Ideation

Among the most dangerous and often-underrecognized symptoms of PMDD is suicidal ideation. Meta-analysis of 13 research studies involving thousands of women found that women with PMDD have 3.95 times higher odds of suicidal ideation compared to those without PMDD. 47 In one comprehensive study of individuals diagnosed with PMDD, researchers found that 72% reported lifetime suicidal ideation, 49% had made suicide plans, and 34% had attempted suicide. Even among women with PMDD who had no other psychiatric diagnoses, rates of suicidal ideation remained extremely elevated.

What makes suicidal ideation in PMDD particularly dangerous is its cyclical, predictable nature combined with high severity. A woman may be functioning adequately and feel stable on day 20 of her cycle, then experience suicidal ideation severe enough to require hospitalization on day 26. The knowledge that this pattern repeats monthly can itself become hopeless. Some women report that as their menstrual cycle approaches, they experience anticipatory dread, knowing that they will enter a period where they will want to end their lives. The fact that suicidal risk is restricted to a defined window (the luteal phase) is both a marker of PMDD and a potential avenue for prevention, as treatment timed to the luteal phase can prevent suicidal crises.

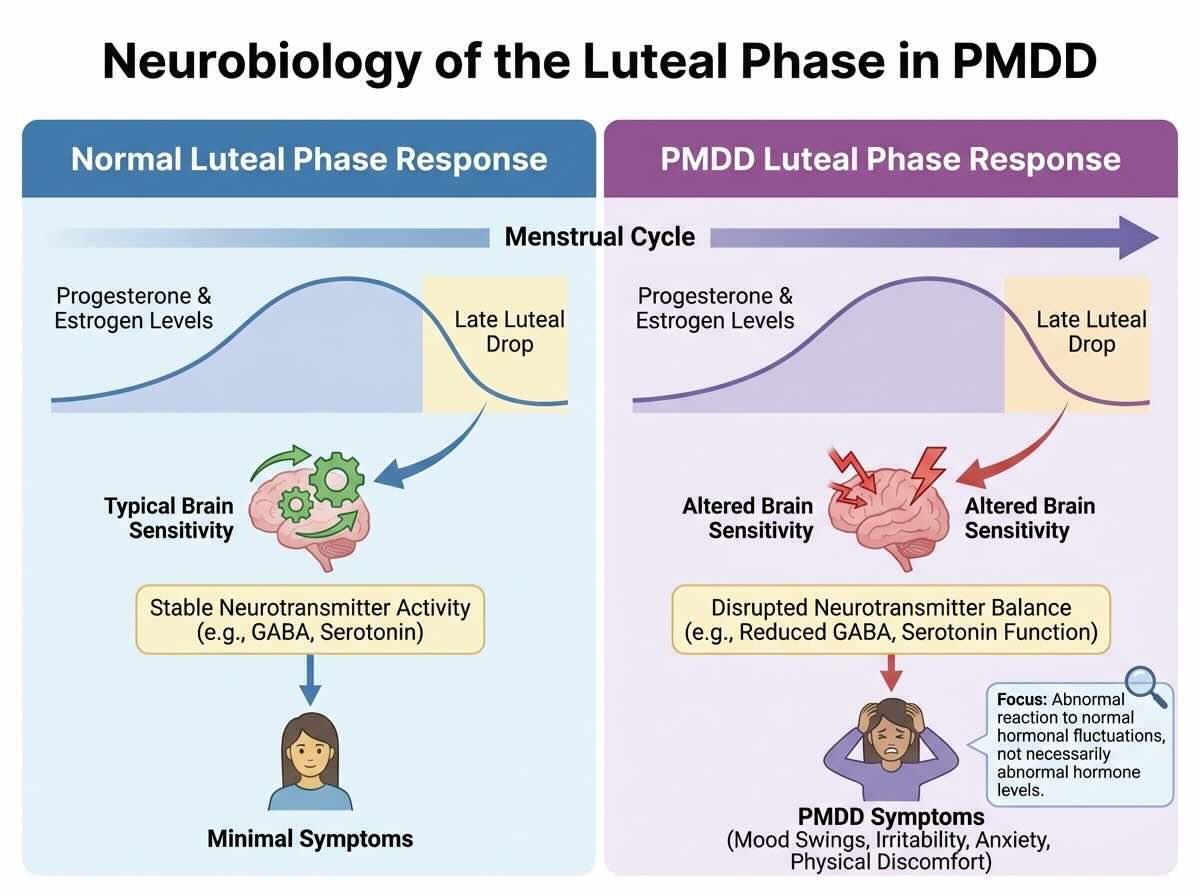

The Neurobiology of PMDD: How the Brain Becomes Hypersensitive to Hormones

The most important scientific development in PMDD understanding over the past two decades is the recognition that PMDD involves abnormal brain sensitivity to normal hormonal fluctuations, not hormone deficiency or abnormal hormone levels. This distinction is crucial because it explains why standard hormone replacement approaches do not work for many women with PMDD, and why approaches targeting the brain’s response to hormones (SSRIs, brain stimulation) are often more effective than approaches targeting hormones themselves (most progesterone supplementation).

Abnormal Sensitivity to Estrogen and Progesterone Fluctuations

In 2017, National Institutes of Health researchers made a breakthrough discovery: women with PMDD possess genetic variations affecting the genes that regulate emotional processing pathways in the brain. These genetic variations confer hypersensitivity to estrogen and progesterone such that normal hormonal fluctuations that other women tolerate without mood change trigger profound mood disruption in PMDD populations. Importantly, hormone levels themselves in women with PMDD are not significantly different from those in women without PMDD. The problem is not how much hormone is present but how the brain perceives and responds to those hormones.

The luteal phase of the menstrual cycle involves specific hormone dynamics: progesterone rises sharply after ovulation, then falls precipitously as menstruation approaches. This fluctuation, which is biologically identical in all menstruating women, triggers mood disruption specifically in women whose brains are genetically primed for hypersensitivity. The falling progesterone levels, rather than the absolute level of progesterone, appear to be the trigger for mood symptoms. This explains why simply supplementing progesterone does not prevent PMDD symptoms in most women: the issue is not insufficient progesterone but abnormal sensitivity to progesterone changes.

Allopregnanolone: The Paradoxical Progesterone Metabolite

One of the most important recent discoveries in PMDD neurobiology involves allopregnanolone (ALLO), a metabolite of progesterone produced in the brain. In the vast majority of women, ALLO acts as a powerful anxiety-reducing neurotransmitter, producing calming and sedative effects. However, in some women with PMDD, ALLO appears to produce paradoxical effects: instead of calming anxiety, it increases anxiety, producing the opposite effect expected from this neurochemical. This paradoxical sensitivity to ALLO may explain why some women experience the most severe anxiety symptoms during the late luteal phase when ALLO levels are highest. Some women describe this as “the hormone that should calm me makes me more anxious,” which captures the fundamental dysregulation in PMDD neurobiology.

This discovery has direct treatment implications: researchers are developing compounds that target ALLO receptor sensitivity or production, with the goal of reversing the paradoxical anxiety response. Clinical trials of a selective brain-penetrating ALLO antagonist have shown promise, suggesting that future treatments targeting this specific mechanism could revolutionize PMDD management.

Serotonin Dysfunction and GABA Sensitivity

Women with PMDD show altered sensitivity to serotonin and GABA, two key neurotransmitters that regulate mood and anxiety. During the luteal phase when progesterone falls, serotonin and GABA levels also decrease. In women with PMDD, this neurochemical decline is more severe or produces more dramatic functional consequences than in women without PMDD. This explains why SSRIs, which increase serotonin availability, are the first-line pharmacological treatment for PMDD: they counteract the serotonin depletion that occurs in the luteal phase.

Inflammatory Pathway Activation

Recent research has identified that women with PMDD show elevated inflammatory markers (including cytokines like interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha) during the luteal phase compared to women without PMDD. This systemic inflammation correlates with both physical symptoms (joint and muscle pain, headaches) and mood symptoms (depression, anxiety). The source of this inflammatory activation in PMDD remains under investigation, but it may involve altered immune response to hormone fluctuations, altered intestinal barrier function, or other mechanisms. This inflammatory pathway suggests that anti-inflammatory interventions might benefit some women with PMDD, though research in this area is still developing.

Brain Structure and Function Differences

Neuroimaging studies have found subtle structural and functional differences in the brains of women with PMDD compared to controls. These include altered connectivity in regions involved in emotional regulation, altered gray matter volume in regions associated with mood processing, and differences in how the amygdala (the brain’s emotion center) responds to emotional stimuli. These structural differences suggest that PMDD involves not simply a biochemical abnormality that SSRIs can correct, but potentially a neurobiological difference in brain organization and function that may have genetic origins.

Genetic and Environmental Vulnerability Factors

PMDD runs in families, with daughters of women with PMDD showing substantially elevated risk themselves, indicating a genetic component. Additionally, environmental factors influence PMDD severity and onset: women with histories of physical or sexual abuse show higher PMDD prevalence; smokers show increased severity; obesity correlates with increased PMDD risk; and women with prior mood disorders (depression, anxiety) are at higher risk for developing PMDD or experiencing more severe PMDD symptoms. This gene-environment interaction model suggests that PMDD emerges in individuals with genetic predisposition when exposed to certain environmental stressors or vulnerabilities.

Diagnosis of PMDD: The Prospective Documentation Requirement

One of the most clinically important and often-missed aspects of PMDD diagnosis is that reliable diagnosis requires prospective symptom tracking over at least two menstrual cycles. This requirement exists because retrospective recall of premenstrual symptoms is notoriously inaccurate: people tend to overestimate premenstrual symptom severity and underestimate symptoms during other phases of the cycle, leading to misdiagnosis of conditions that are not actually cyclical as PMDD. Only prospective tracking can establish the temporal relationship between symptoms and menstrual phase.

Diagnostic Criteria: The Specific Requirements

According to the DSM-5, PMDD diagnosis requires the following:

Criterion A (Cyclical Timing): In the majority of menstrual cycles, at least five symptoms must be present during the final week before menstruation onset; begin to improve within a few days after menstruation starts; and become minimal or absent in the week after menses.

Criterion B (Mandatory Mood Component): At least one of four key mood symptoms must be present: marked affective lability (mood swings), marked irritability or anger, marked depressed mood, or marked anxiety or tension. This requirement ensures that PMDD involves affective disruption, distinguishing it from conditions characterized by physical premenstrual symptoms alone.

Criterion C (Total Symptom Count): At least five symptoms total must be present, including one from the mandatory mood category and four others from the list of possible symptoms. The remaining symptoms may include decreased interest in activities, difficulty concentrating, lethargy, appetite/sleep changes, sense of being overwhelmed, or physical symptoms such as breast tenderness, joint pain, bloating, or headaches.

Criterion D (Functional Impairment): The symptoms must cause clinically significant distress or interference with work, school, social activities, or relationships. This criterion prevents diagnosis of mild premenstrual symptoms that do not meet the severity threshold.

Criterion E (Exclusion of Other Causes): The symptoms are not exacerbations of another untreated mental disorder (such as major depressive disorder), though PMDD can co-occur with other psychiatric conditions.

Criterion F (Prospective Confirmation): Diagnosis must be confirmed by prospective daily tracking of symptoms for at least two menstrual cycles using a standardized instrument or daily diary. Retrospective reports alone are insufficient for reliable diagnosis.

Criterion G (Medical Exclusion): The symptoms must not be attributable to substance use, medications (including contraceptives in some cases), or another medical condition such as thyroid disorder, which can cause mood symptoms.

The Clinical Assessment Process

A proper PMDD assessment involves several components. First, the clinician takes a detailed reproductive history including age of menarche, menstrual cycle regularity, history of mood symptoms, family history of PMDD or depression, trauma history, and prior treatments attempted. Second, the clinician explains the need for prospective tracking and provides the individual with a symptom tracking tool, typically a daily diary or smartphone application that captures mood, energy level, specific symptoms, and functional impact each day. Third, at least two full menstrual cycles of tracking are completed (roughly 60 days of daily tracking). Fourth, the clinician reviews the tracking data to confirm the cyclical pattern: symptoms clustering in the luteal phase with resolution after menstruation. Fifth, the clinician assesses functional impairment across work, school, relationships, and self-care. Finally, the clinician rules out medical causes (thyroid, other endocrine disorders) and other psychiatric conditions that might better explain the symptoms.

This rigorous diagnostic process is necessary because misdiagnosis of other conditions as PMDD, or misdiagnosis of PMDD as generalized mood disorder, leads to ineffective treatment. A woman with bipolar II disorder whose mood episodes happen to cluster around her menstrual cycle might be misdiagnosed with PMDD and treated with SSRIs alone, missing the need for mood-stabilizing medications. Conversely, a woman with PMDD might be diagnosed with major depressive disorder and treated with continuous antidepressants when luteal-phase dosing would be sufficient and involve lower medication exposure. Accurate diagnosis is essential for appropriate treatment.

Suicide Risk in PMDD: The Magnitude of the Crisis

The association between PMDD and suicide is among the most consistent and severe psychiatric risk factors in mental health research. Multiple large meta-analyses have documented this relationship with remarkable consistency: women with PMDD carry dramatically elevated suicide risk compared to the general population, and this risk persists even after controlling for comorbid psychiatric conditions. Understanding the magnitude of this risk is essential for clinicians, patients, and public health authorities because it elevates PMDD from a quality-of-life concern to a genuine psychiatric emergency for affected women.

Quantifying the Suicide Risk: Meta-Analytic Evidence

A 2021 meta-analysis examining 13 studies with a total of 8,532 participants found that women with PMDD have 6.97 times higher odds of suicide attempt (95% confidence interval 2.98 to 16.29) and 3.95 times higher odds of suicidal ideation (95% confidence interval 2.97 to 5.24) compared to women without PMDD. These are among the highest odds ratios documented for any risk factor in psychiatry. For perspective, the odds ratio for suicide attempt in bipolar I disorder is typically 4 to 5; PMDD’s 6.97 times risk exceeds even this extreme psychiatric condition.

A separate meta-analysis by Yan and colleagues found slightly lower but still extremely elevated risk: odds ratio of 2.34 for suicidal ideation, 2.13 for suicide attempts, and 2.24 for suicide planning. The variation between meta-analyses likely reflects differences in which studies were included and how stringent the diagnostic criteria were, but all analyses converge on the conclusion that PMDD carries independent, substantial suicide risk.

The Clinical Reality: Lifetime Rates of Suicidality in PMDD Populations

In a landmark 2022 study led by Tory Eisenlohr-Moul at the University of Illinois Chicago, researchers assessed a large sample of individuals diagnosed with PMDD and found extraordinarily high rates of suicidality: 72% reported lifetime active suicidal ideation, 49% had made suicide plans, 42% reported suicide intent, 40% reported preparing for suicide attempts, and 34% had made suicide attempts. Additionally, 51% reported non-suicidal self-injury. These rates are substantially higher than observed in major depressive disorder or other psychiatric conditions.

Critically, among the PMDD participants who reported suicidal ideation, those without comorbid depression or PTSD still reported extremely elevated rates: 65% with suicidal ideation even without depression, 48% with plans, 34% with attempts. This finding demonstrates that the suicide risk in PMDD is not merely a reflection of comorbid depression. Rather, PMDD itself carries independent suicide risk.

Temporal Specificity: Suicidal Crises in the Luteal Phase

A defining feature of suicidality in PMDD is its cyclical, predictable timing. Women with PMDD often experience suicidal ideation exclusively or predominantly during the luteal phase, with ideation resolving or substantially diminishing after menstruation begins. Some women describe being able to predict almost to the day when suicidal thoughts will emerge. This temporal specificity is both a warning sign that distinguishes PMDD-related suicidality from other psychiatric conditions and a potential leverage point for prevention. Because the high-risk window is predictable, preventive interventions timed to the luteal phase can be deployed.

Risk Factors That Further Elevate Suicide Risk in PMDD

The Eisenlohr-Moul study identified additional predictors of suicide attempts and ideation in PMDD populations: low-to-moderate income (suggesting that economic stress compounds PMDD burden), prior major depressive episode, prior PTSD, and nulliparity (never having given birth). Older age and borderline personality disorder were additional predictors of suicide attempts. These findings suggest that women with PMDD plus additional vulnerability factors (poverty, prior trauma, older age, comorbid personality disorder) warrant particularly intensive monitoring and treatment.

Clinical Implications: Why PMDD Must Be Recognized as a Psychiatric Emergency

The magnitude of suicide risk in PMDD necessitates that the condition be recognized as a serious psychiatric disorder rather than dismissed as a quality-of-life concern or hormonal issue. Any woman presenting with suicidal ideation that follows a menstrual cycle pattern should be assessed for PMDD. Conversely, any woman diagnosed with PMDD should be systematically assessed for suicidal ideation and planning, particularly during the luteal phase. Treatment of PMDD can be literally lifesaving, making proper diagnosis and treatment not only quality-of-life matters but suicide prevention measures.

The Real-World Burden: How PMDD Disrupts Work, School, and Relationships

While suicide risk represents the most acute danger of PMDD, the chronic functional impairment caused by the condition generates substantial burden across multiple life domains. Research quantifying this burden reveals the extent to which PMDD disrupts productivity, economics, and quality of life.

Work and School Impairment

In a 2021 study examining quality of life in women with PMDD, researchers found that 100% of PMDD participants reported fatigue or lack of energy, compared to only 67% of those with no or mild premenstrual syndrome. Over 70% of PMDD participants reported impairment in work or school productivity, making it the most frequently affected domain of functioning. The exhaustion and cognitive dysfunction combine to make work performance during the luteal phase substantially worse than during other phases of the cycle.

Women with PMDD miss more than 8 hours per menstrual cycle due to inability to function. Over a year, this accumulates to roughly 20-24 hours of absenteeism per woman. Indirect costs of both absenteeism (days missed) and presenteeism (attending work but unable to perform at full capacity) were estimated at over 4,000 US dollars annually per woman with premenstrual symptoms severe enough to impact productivity. For the approximately 2.3 million American women with PMDD, this represents an aggregate economic burden of roughly 9.2 billion US dollars annually in lost work productivity alone.

Relationship Disruption and Family Impact

A large 2024 study following over 15,000 women from 2009 to 2021 found that those with PMDD had a 22% higher risk of relationship disruption (defined as ending of a romantic relationship through divorce, separation, or breaking up with a cohabitating partner) compared to those without severe premenstrual symptoms. Notably, this elevated risk was present even among women without depression or anxiety, confirming that PMDD itself, independent of comorbid mental health conditions, increases relationship rupture risk.

The mechanism through which PMDD damages relationships is the severe irritability and anger during the luteal phase. Partners become targets for disproportionate rage and criticism. Relationships that otherwise function well experience acute crisis during the luteal phase. Some women describe their partners “walking on eggshells” during these weeks, monitoring speech and actions to avoid triggering an emotional explosion. The cumulative damage of repeated monthly cycles of conflict, followed by remorse and apology after menstruation, creates relationship strain that eventually exceeds what many partnerships can sustain.

Additionally, women with PMDD often withdraw socially during the luteal phase, canceling plans, avoiding friends, and isolating due to the combination of depressed mood, anxiety, and inability to engage socially. Over time, social relationships deteriorate from this repeated withdrawal pattern.

Healthcare Utilization Burden

Women with PMDD show substantially increased healthcare utilization. Research has documented that PMDD increases the likelihood of visiting a specialist physician three or more times during a 12-month period, implying both economic costs through medical care and emotional burden of navigating healthcare systems seeking help for cyclical symptoms. The high healthcare utilization likely reflects both appropriate treatment-seeking and the substantial distress that prompts women to seek medical intervention.

Quality of Life: A Comprehensive Deterioration

Beyond specific work or relationship metrics, PMDD produces pervasive deterioration in quality of life. Women report that approximately two to four weeks per month are lost to a condition over which they have no control. They cannot plan activities with confidence (will they be in a depressive, suicidal phase when this event occurs?). They lose career opportunities due to reduced productivity during luteal phases. They experience shame and guilt about their rage and withdrawal hurting loved ones. They face repeated skepticism from healthcare providers who minimize premenstrual mood symptoms as “normal” or “just hormones.” Over years, the accumulated burden of lost months, damaged relationships, reduced career progression, and repeated psychiatric crises profoundly impacts overall life trajectory and wellbeing.

Treatment for PMDD: Evidence-Based Interventions That Work

The encouraging reality is that PMDD is highly treatable. Unlike many psychiatric conditions where treatment success is partial or requires ongoing management, PMDD treatment often produces dramatic improvement or complete symptom resolution. Response rates to first-line treatments are substantially higher than for general depression (60-75% experiencing significant improvement versus 50-60% for major depressive disorder), and combination approaches produce even higher response rates.

First-Line Pharmacological Treatment: Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)

SSRIs are the first-line pharmacological treatment for PMDD. Common medications include sertraline, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and citalopram. SSRIs work by increasing serotonin availability, counteracting the serotonin depletion that occurs during the luteal phase in susceptible women. Response rates to SSRIs in PMDD are remarkably high: 60-70% of women experience substantial improvement in mood symptoms.

A critical aspect of SSRI treatment in PMDD is the dosing schedule. SSRIs can be taken continuously (every day throughout the menstrual cycle) or cyclically (only during the luteal phase, typically starting from ovulation or day 14 and continuing through the first day of menstruation). Cyclical dosing is particularly advantageous in PMDD because it minimizes medication exposure. Many women respond exceptionally well to luteal-phase dosing, taking the medication only 14 days per month. This approach reduces medication burden, minimizes potential side effects, and is often more acceptable to women concerned about daily medication use. Some research suggests that cyclical dosing is as effective as continuous dosing in PMDD, though some women require continuous dosing for optimal benefit.

The timeline for SSRI effectiveness in PMDD differs from depression treatment. In major depressive disorder, SSRIs require 4-6 weeks to show benefit. In PMDD, some women experience benefit within 2-3 menstrual cycles, and response can be quite rapid. Additionally, while most SSRI side effects (such as sexual dysfunction or emotional blunting) develop over time, these side effects are less problematic with cyclical dosing since medication exposure is limited.

Different SSRIs have varying evidence bases for PMDD, though all are likely effective. Sertraline and fluoxetine have the most robust evidence from randomized controlled trials. Some women may require trial-and-error to identify which SSRI works best, as response is individual.

Hormonal Contraception

Combined hormonal contraceptives (containing both estrogen and progestin) can effectively treat PMDD by suppressing ovulation and eliminating the hormonal fluctuations that trigger symptoms. The suppression of the progesterone surge and subsequent decline that occurs in ovulatory cycles removes the hormonal trigger of symptoms. Extended-cycle or continuous-cycle hormonal contraceptives (with fewer or no hormone-free intervals) are typically more effective for PMDD than traditional monthly-cycle pills. Some progestins are more PMDD-friendly than others; norethindrone-based or dydrogesterone-based formulations may produce less mood disruption than older progestins.

For many women, hormonal contraception alone provides sufficient symptom control. For others, PMDD symptoms persist despite hormonal contraception, necessitating combination treatment with an SSRI. Approximately 60% of women achieve adequate symptom control with hormonal contraception alone.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Psychotherapy, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), is effective for PMDD, particularly when combined with medication. CBT for PMDD targets several mechanisms:

- identifying and modifying catastrophic thinking that amplifies mood symptoms (“Everything will always be this way,” “I’m a terrible person”),

- developing coping strategies specific to the luteal phase (increased self-compassion, boundary-setting with others, planned activities that provide structure and mild pleasure),

- addressing lifestyle factors such as sleep, exercise, and stress that can modulate symptom severity, and

- improving communication in relationships so partners understand the cyclical nature of PMDD and develop realistic expectations during the luteal phase.

Research shows that CBT combined with medication produces superior outcomes to either intervention alone. The therapy provides skills and cognitive tools that reduce symptom severity and help individuals manage the psychological impact of living with PMDD.

Lifestyle and Behavioral Interventions

While lifestyle changes alone are insufficient to treat PMDD, they support medication and therapy and can modulate symptom severity. Evidence-based lifestyle interventions include:

- regular aerobic exercise (at least 30 minutes most days), which increases serotonin and endorphins;

- consistent sleep schedules with attention to sleep quality, particularly important because sleep disruption is prevalent in PMDD and sleep deprivation worsens mood;

- dietary calcium and magnesium supplementation, with research showing that calcium supplementation (1200mg daily) and magnesium (360mg daily) reduce PMDD symptom severity;

- reducing caffeine and sugar, which can destabilize mood; and

- stress reduction through meditation, yoga, deep breathing, or other relaxation techniques.

These interventions are accessible, low-cost, and support overall wellbeing beyond PMDD treatment. Women often find that combining medication, therapy, and lifestyle changes produces the best outcomes.

Specialized Pharmacological Treatment for Severe, Treatment-Resistant PMDD

For women who do not respond to SSRIs or hormonal contraception, several specialized options exist. GnRH (gonadotropin-releasing hormone) agonists suppress ovulation completely, eliminating hormonal cycling and PMDD symptoms entirely. However, GnRH agonists produce a temporary menopausal state with associated hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and bone density concerns, making them appropriate only for severe, treatment-resistant PMDD.

Newer treatments targeting ALLO (allopregnanolone) dysfunction are in development and show promise. Additionally, research continues on other mechanisms (inflammatory pathway modulation, targeted psychotherapy) that may benefit subsets of women with PMDD.

Treatment Response and the Importance of Persistence

Overall, 60-75% of women with PMDD experience significant improvement with first-line treatments. For the 25-40% who do not respond to initial treatment, adjusting medication dose, switching to a different SSRI, combining SSRI with hormonal contraception, or adding psychotherapy typically produces improvement. Very few women are truly treatment-resistant if appropriate interventions are systematically tried.

The key to successful treatment is accurate diagnosis followed by systematic trial of evidence-based interventions. Many women with PMDD suffer for years without adequate treatment not because treatment is ineffective but because they are misdiagnosed or their cyclical symptoms are dismissed. Recognition of PMDD by healthcare providers and commitment to proper diagnosis and treatment can transform the lives of millions of women.

Key Takeaway

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder is a serious psychiatric condition affecting approximately 2.3 million American women annually, characterized by severe mood disruption, suicidal ideation, and profound functional impairment that occurs cyclically during the menstrual cycle’s luteal phase. PMDD reflects abnormal brain sensitivity to normal hormonal fluctuations rooted in genetic and neurobiological differences, not personal weakness, hormonal deficiency, or simple bad mood. The condition carries extraordinary suicide risk, with women experiencing 6.97 times higher odds of suicide attempt and 3.95 times higher odds of suicidal ideation compared to non-PMDD populations.

Beyond acute suicide risk, PMDD damages work productivity, relationships, and overall quality of life through severe mood symptoms, cognitive dysfunction, and fatigue. However, PMDD is highly treatable: 60-75% of women achieve significant improvement with first-line treatments including SSRIs (particularly luteal-phase dosing), hormonal contraception, and cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Accurate diagnosis requires prospective symptom tracking over two menstrual cycles, but once confirmed, evidence-based treatment can be literally lifesaving and substantially improve functioning. Every woman experiencing cyclical mood symptoms severe enough to disrupt functioning, particularly those with suicidal ideation, deserves professional assessment and evidence-based treatment.

The recognition of PMDD as a psychiatric disorder requiring clinical intervention remains underutilized, leaving millions of women suffering unnecessarily from a highly treatable condition.

Research References

All statistics, diagnostic criteria, and treatment information in this article are based on peer-reviewed research, meta-analyses, and clinical guidelines published 2021-2025. Click links for primary sources.

- Islas-Preciado D, et al. Unveiling the burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2025;16:1458114. PMID: 38290165. Comprehensive narrative review of global PMDD burden, prevalence disparities, and systemic barriers to diagnosis.

- Gao M, et al. Global and regional prevalence and burden for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2022;230:174-183. PMID: 35033735. Global prevalence meta-analysis showing 2-8% PMDD prevalence globally with substantial regional variation.

- Yan et al. Suicidality in women with PMDD: Meta-analysis. Women’s Mental Health. 2022. Meta-analysis of suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts in PMDD populations.

- Charlie Health PMDD Research Report. 2025 Update on PMDD epidemiology and burden. Comprehensive data showing 2.3 million U.S. women with PMDD, 22% increased relationship disruption risk, productivity costs.

- Yan H, et al. Suicidal Risk in Women with Premenstrual Syndrome and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;295:431-438. PMID: 34875392. Meta-analysis of 13 studies showing 6.97x higher suicide attempt risk and 3.95x higher ideation risk in PMDD.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). PMS/PMDD: An Update. 2025. Clinical guidelines from RCOG documenting PMDD prevalence 5-8%, WHO ICD-11 recognition, treatment approaches.

- Epperson CN, et al. Making Strides to Simplify Diagnosis of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Journal of Women’s Health. 2016;25(4):348-355. PMID: 27010075. Diagnostic criteria clarification and prospective tracking methodology.

- Office on Women’s Health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD). Updated 2025. Official U.S. government health resource on PMDD definition, symptoms, and diagnosis.

- Flo Health. PMDD vs. PMS: Key Differences. Updated 2025. Comparative analysis of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Management of Premenstrual Syndrome and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Updated 2023. Official clinical guidelines on PMDD treatment and first-line management.

- University of Illinois Chicago. Eisenlohr-Moul T et al. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors linked to hormone-sensitive brain disorder. June 2022. Landmark study of 5,000+ PMDD individuals showing 72% lifetime suicidal ideation, 49% plans, 34% attempts.

- DSM-5 Prevalence Estimates. The Relationship Between Premenstrual Dysphoric Symptoms. November 2025. DSM-5 diagnostic criteria and prevalence estimates 1.8-5.8% annual PMDD in U.S.

- PsychDB. Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder Clinical Primer. Updated 2025. Comprehensive clinical overview including neurobiological mechanisms, diagnostic criteria, treatment approaches.

Experiencing Cyclical Mood Crises? Professional Treatment Can Help

Still Mind Behavioral Mental Health specializes in diagnosing and treating PMDD and other mood disorders with cyclical patterns. Our Fort Lauderdale team provides comprehensive assessment, including prospective symptom tracking, medication management, and cognitive-behavioral therapy specifically designed for PMDD treatment.

Still Mind Behavioral Mental Health

Fort Lauderdale, Florida

Expert diagnosis and evidence-based treatment for PMDD